Section 3.2

Linking Wetland Plant Functional Traits to Disturbance

Summary of the influence of plant functional traits on wetlands' resistance to invasion by terrestrial plant species

Diane Haughland

Diane Haughland

Rough Hair Grass is a ruderal species (i.e., early colonizer)—a functional trait indicative of disturbed areas that are more susceptible to invasive species.

- Functional traits (e.g., leaf area and mean seed weight) are quantifiable traits that relate to a plant’s ecological role.

- Functional traits of native species may influence how resistant a given wetland is to environmental pressures such as disturbance or invasive species.

- We used various datasets to examine how wetland plant functional traits, the environment surrounding a wetland, and the distribution of two terrestrial weeds—Canada Thistle and Perennial Sow-thistle—are related.

- Differences in the composition of functional traits (e.g., stress tolerance and hydrophyte status) were observed to correlate with the distribution of these invasive species.

- Full study results are available in Allen et al. 2021[1].

Introduction

Biodiversity—the variety of life in a given area—is influenced by countless relationships among species, and their interactions with the environment in which they occur.

- From this perspective, species are the sums of their functional traits—the ecological functions they fulfill—and there is increasing evidence that the composition and the diversity of the traits in an ecological community (functional diversity) can say a lot about how that community might respond to changes in its environment.

- Research suggests that some combinations of functional traits are more resistant than others to the effects of environmental pressures such as disturbance or the advance of invasive species. This has implications for management: if you figure out the combination of functional traits that promotes resilience, you might be in a better position to prioritize what, and how, to manage.

Functional traits, like leaf area, relate to a plant's ecological role.

The right combination of functional traits can increase a wetland's resistance to terrestrial invasive species.

In this study, we examined what combination of plant functional traits was associated with wetlands that appear to be more resistant to invasion by terrestrial species.

More about Functional Traits

Functional traits are quantifiable traits that relate to a plant’s ecological role.

- Seed weight is an example of a functional trait that relates to the dispersal and competitive abilities of a plant.

- Large seeds provide extra resources, giving seedlings a head start. This is beneficial in environments where resources are scarce.

- Where resources are readily available, producing more smaller seeds might be a better strategy to establish more seedlings.

- Examining the trade-off inherent in functional traits can yield insight into the niche that each plant is filling.

Common Dandelion is a familiar example of a plant that produces large numbers of small seeds.

The presence of water-loving plants such as Round-leaved Sundew can indicate that a wetland is more resistant to terrestrial invasive species.

Examining the prevalence of certain functional traits across a plant community can yield insight into the ecology of the community as a whole—for example, its ability to resist invasive species.

- Hydrophyte status is a functional trait that indicates a plant’s degree of dependence on wet conditions. A high prevalence of hydrophytes in a specific wetland indicates that the wetland is more likely to be consistently inundated with water, making it less likely that terrestrial species—like invasive plants—can establish and spread.

- Conversely, a high prevalence of ruderal species (species that are adapted to colonize disturbed habitat) would indicate that a wetland is prone to disturbance, making it more likely to be invaded.

Methods

Focusing on Alberta’s boreal wetland plant communities, we used various datasets from the Alberta Biodiversity Monitoring Institute (ABMI) and other sources to investigate the interplay between:

- the diversity and composition of plant functional traits—such as growth habit (e.g., grass, shrub, tree) and strategy type (e.g., competitor, stress tolerator, ruderal)—in boreal wetlands,

- the properties of the local environment, and

- the distribution of two noxious terrestrial invasive weeds in Alberta—Canada Thistle (Cirsium arvense) and Perennial Sow-thistle (Sonchus arvensis).

For detailed methods, see Allen et al. 2021[1].

| Ecological Characteristic | Functional Trait |

|---|---|

| Competitive ability |

Maximum height Leaf dry matter content Specific leaf area Leaf size |

| Dispersal and establishment ability | Mean seed weight |

| Species' response to disturbance |

Grime strategy type (competitor, stress tolerant, ruderal) Life span Growth form |

| Species' affinity for occupying wetlands | Regional hydrophyte status (facultative wetland or obligate wetland status) |

| Group | Variable |

|---|---|

| Land cover matrix |

Urban/Industrial Cultivation Successional Deciduous mixedwood Pine Lowland coniferous Wetland |

| Water chemistry |

pH Salinity Total nitrogen Total phosphorus Dissolved organic carbon |

| Climate |

Frost-free period Mean annual precipitation |

Canada Thistle

Perennial Sow-thistle

Results

There are three main takeaways from this study:

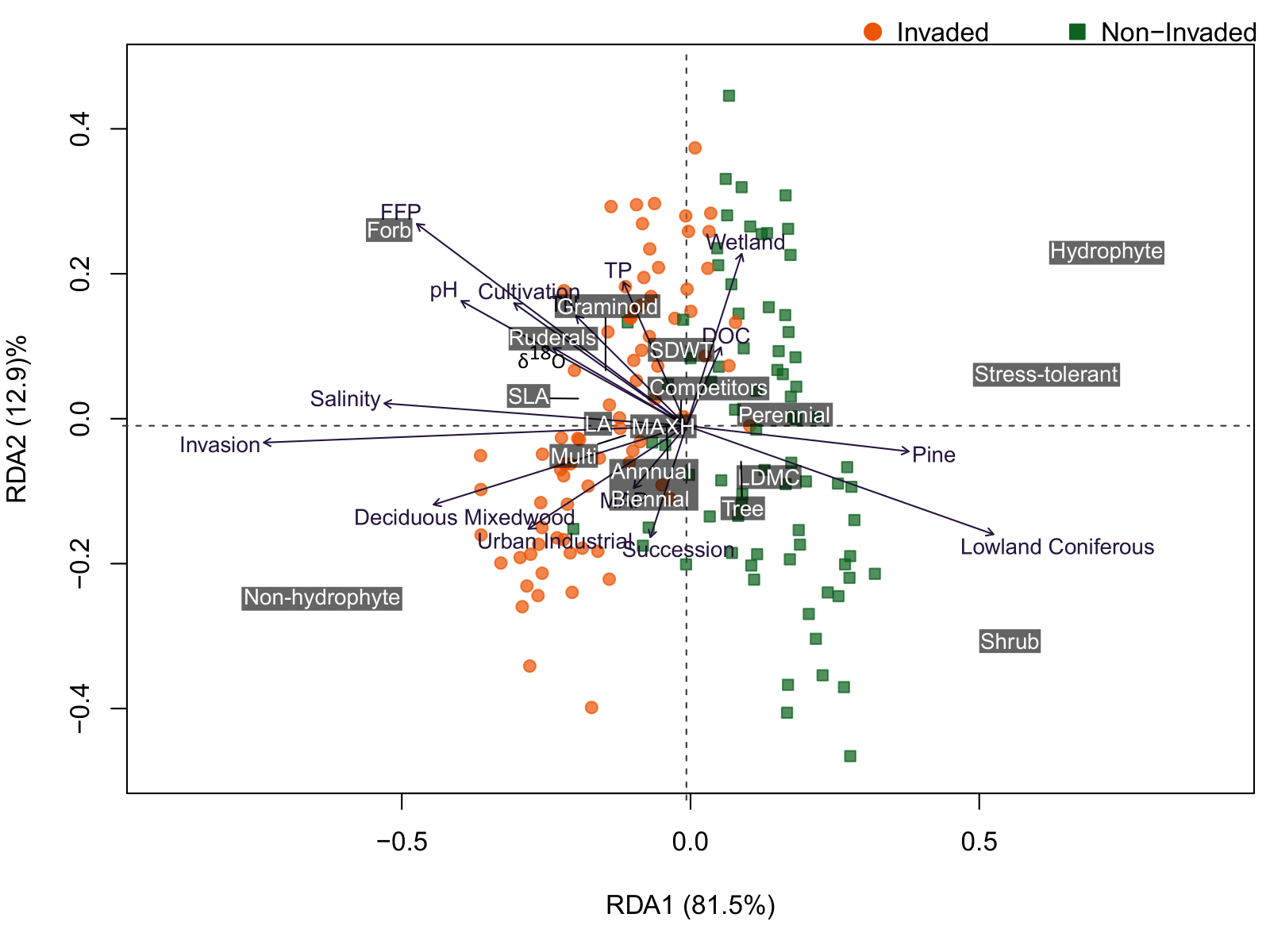

- First, wetlands without terrestrial invasive species (represented by green squares in the graph) tended to be dominated by plants that were hydrophytes (water-loving) and stress tolerant—such as Round-leaved Sundew (Drosera rotundifolia) and Bulb-Bearing Water Hemlock (Cicuta bulbifera). These functional traits indicate an environment that tends to stay inundated and is nutrient limited—in this case stable wetlands surrounded by lowland conifer and pine forests—making it more difficult for upland species to invade.

- Second, wetlands with terrestrial invasive species (represented by orange circles in the graph) tended to be surrounded by human footprint and to include plants that are ruderals—such as Rough Hair Grass (Agrostis scabra) and Toad Rush (Juncus bufonius). These types of plants are often associated with disturbance and invest in high seed production and rapid reproduction, indicating an environment that would be easier for other species to invade.

- Third, though total functional trait richness and diversity did not vary between invasion status, we observed large differences in the composition of functional traits between invaded wetlands and non-invaded wetlands. This means that invasion resistance isn’t about the absolute number of species present, but rather about having the right ones.

Results of the community weighted means redundancy analysis where we examine the relationships between species traits, land cover, invasion, water chemistry, and spatial and climate variables. In general, sites without terrestrial invasive species are positively associated with variables on the right side of the x-axis, while invaded sites are positively associated with variables on the left side of the x-axis. Environmental variables are represented with a white background (TP = total phosphorus, TN = total nitrogen, DOC = dissolved organic carbon, FFP = frost-free period, MAP = mean annual precipitation). Species traits are represented with a grey background (SLA = specific leaf area, LA = leaf area, SDWT = mean seed weight, MAXH = maximum height).

For full study results, see Allen et al. 2021[1].

Conclusion

- Though only scratching the surface of the observed relationships, the results in this study give a unique snapshot of plant functional trait composition and diversity across wetlands in Alberta’s boreal region, and the resistance of those wetlands to terrestrial invasive plants.

- The team hopes that the results will help lay the groundwork for predicting whether a given wetland community will resist or shift in response to ongoing and future environmental pressures.

- For example, a specific lowland/wetland habitat matrix may be more resistant to invasion by terrestrial species but less resilient once invasive species have established; this kind of information could be taken into consideration in land use planning.

References and Additional Support

References

Allen, B.E., E.T. Azeria, and J.T. Bried. 2021. Linking functional diversity, trait composition, invasion, and environmental drivers in boreal wetland plant assemblages. Journal of Vegetation Science 32(5):e13073. https://doi.org/10.1111/jvs.13073

Additional Resources

Illerbrun, K. 2021. Taking it littoral-y: untangling what shapes Alberta’s boreal wetland plant communities. Alberta Biodiversity Monitoring Institute blog. http://blog.abmi.ca/2021/10/04/taking-it-littoral-y-untangling-what-shapes-albertas-boreal-wetland-plant-communities/#.YbD6W73MJMs

Contributors

Brandon Allen

Brandon Allen, Senior Terrestrial Ecologist, Alberta Biodiversity Monitoring Institute (ABMI)

Brandon joined the ABMI in 2016. He currently leads the development of multiple landscape-scale biodiversity indicators and has become passionate about amphibians.

If you have questions about wetland plant functional traits, please get in touch: brandon.allen@ualberta.ca