Section 4.2

Status of Amphibians

Summary of the occurrence of the frog and toad species found in Alberta's wetlands. Analysis includes habitat associations and calling activity for four species.

Autonomous recording units are used to monitor the breeding calls of frogs and toads. The acoustic data are used to understand species' distributions and to model species–habitat relationships for common amphibians.

Boreal Chorus Frog

68.8% occurrence

Commonly detected in a variety of wetland and human footprint types.

Canadian Toad

16.1% occurrence

Abundance is low in most human footprint types.

Western Toad

11.5% occurrence

Most abundant in native mid-aged pine and deciduous forests and old black spruce forests.

Wood Frog

41.9% occurrence

Commonly detected in a variety of habitat, wetland, and human footprint types.

Introduction

Amphibians around the world are on the decline because of habitat loss, contaminants, disease and climate change.

- Amphibians are vulnerable to both direct and indirect effects of habitat loss and degradation[1], which includes sensory disturbance from increased noise levels[2].

- Because amphibians have both aquatic and terrestrial life stages, they can provide early warnings of changes in both types of environments.

- There are ten species of amphibians in Alberta. Eight of these (frogs and toads) can be reliably detected using acoustic monitoring, which records their breeding calls.

- The remaining two species—both salamanders—do not vocalize during the breeding season. See the methods spotlight on amphibian eDNA to learn about alternate monitoring methods for cryptic, “silent” species.

In this section, we use acoustic data to examine amphibian distribution in Alberta, activity levels, and associations with habitat and human footprint types.

Northern Leopard Frog inhabits a variety of habitats; it is at risk in Alberta.

Plains Spadefoot is limited to sandy soils, which it digs into with its large hind feet.

Columbia Spotted Frog is highly aquatic, and even hibernates underwater.

Methods

- The ABMI began deploying autonomous recording units (ARUs) in 2015 to capture vocalizing amphibians.

- In collaboration with the Bioacoustic Unit, we have compiled more than 14,000 recordings of amphibian calls from 1,648 unique locations across Alberta.

- These observations have been incorporated into the ABMI's species distribution modelling framework that identifies species–habitat relationships with native land cover, human footprint and climate.

- We present results for four amphibian species that occur throughout Alberta: Boreal Chorus Frog (Pseudacris maculata), Canadian Toad (Anaxyrus hemiophrys), Western Toad (Anaxyrus boreas) and Wood Frog (Lithobates sylvaticus), along with occurrence information for the rarer frog and toad species.

- The model results include distribution for the four species, the seasonality of their breeding calls, and habitat associations within the forested and prairie regions of Alberta.

- For field sampling protocols see ABMI 2019[3], and for analysis methods see ABMI 2022[4].

An autonomous recording unit (ARU) installed in a wetland to detect frogs and toads that call during the breeding season.

- Some explanatory variables may be confounded with each other. The ABMI collects observation data—we do not manipulate levels of habitat and human footprint types at our sites. This means that some variables may be confounded, such as the effects of latitude and agricultural footprint on occurrence.

- Our species distribution models are created through batch processing by taxonomic group. This means that all species within a given taxonomic group (e.g., amphibians, mosses) are modeled using the same combination of environmental variables (e.g., habitat types, human footprint types, climate), even though there may be a more appropriate combination for specific species.

- The vegetation and soil layers we use in our models are based on GIS analysis. No GIS product has 100% accuracy. Errors in classification could lead to inaccuracies in our predictions of species’ distributions.

- We currently don't include effects outside of direct habitat loss in our models. We know that many species respond to impacts such as edge effects, grazing, pollution, or alteration in groundwater flows. We are continuing to improve our species–habitat models to include additional effects, but our models are unable to include all possible impacts on species abundance.

Results

To view occurrence and model results for frog and toad species in Alberta, select from the tabs below.

Introduction

- The Boreal Chorus Frog is common in Alberta, occurring in all natural regions and nearly every habitat except for alpine environments.

- It breeds in a range of small, shallow bodies of water such as wet meadows, woodland ponds, swamps, and flooded ditches.

- The Boreal Chorus Frog also uses a range of moist terrestrial habitats near these wetland breeding areas, and hibernates in abandoned burrows and other cavities below the frost line.

The call of the Boreal Chorus Frog sounds like a fingernail running along a plastic comb.

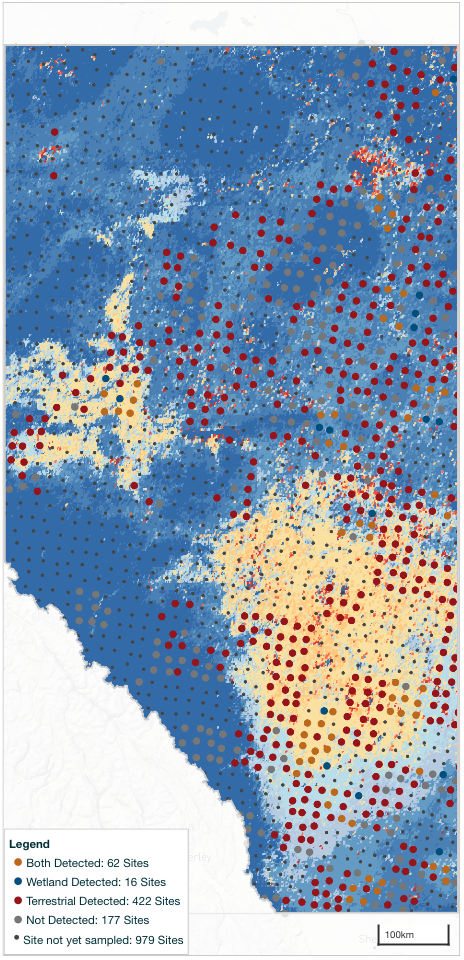

Distribution

- Boreal Chorus Frog was detected at 68.6% of 1,648 survey locations.

- Most suitable habitat is found throughout the Grassland and Parkland natural regions.

Breeding Habitat

Richard Bukowski

Richard Bukowski

This pond in the parkland is an example of suitable breeding habitat for Boreal Chorus Frog.

(LOW) 0 100 (HIGH)

Seasonality

- Boreal Chorus Frogs hibernate during the winter, and are able to withstand sub-freezing temperatures.

- Males begin calling to attract females in early spring, with the exact dates varying by latitude—occurring earlier in the south because of warmer temperatures.

- In Alberta, we detected Boreal Chorus Frogs vocalizing from mid April to mid July, with a peak calling frequency in early June.

We present modelling results for the Boreal Chorus Frog in the forested and prairie regions. In both areas, Boreal Chorus Frog was abundant in a variety of forest, vegetation, and human footprint types.

- Boreal Chorus Frog is abundant in both native wetlands and human footprint.

- Boreal Chorus Frog is most abundant in human footprint land cover types, including crops, rough pasture, tame pasture, and urban/industrial footprints.

- Boreal Chorus Frog is also abundant in native wetland (bogs, fens, swamps) and open upland (grass, shrub) habitats.

- Interestingly, Boreal Chorus Frog is also relatively abundant in young harvest areas. These habitats could have altered landscape properties that allow for shallow ephemeral ponds to form, thus creating attractive breeding sites.

- While the Boreal Chorus Frog appears to be fairly adaptable to disturbance in the forested region, ARU data does not provide information on how successful breeding is at a given site or whether the site is viable in the long term.

- Boreal Chorus Frog relative abundance is similar at non-treed and treed sites.

- Boreal Chorus Frog is abundant across sites with native soils and sites with human footprint in the prairie region.

Introduction

- The Canadian Toad has been detected in the Boreal Forest, Parkland and Grassland natural regions, and is distributed throughout the eastern portion of Alberta.

- It breeds in wetlands, slow-flowing streams, and ditches that are located in open areas, such as prairies and aspen parkland, instead of forests.

- Outside of the breeding season, the Canadian Toad is rarely in water. It prefers terrestrial environments with high humidity and moist soils.

- Canadian Toads hibernate during the winter; they usually burrow in sandy soils, deep enough to avoid freezing.

Because of declines in population and distribution, Canadian Toad is considered May Be at Risk in Alberta.

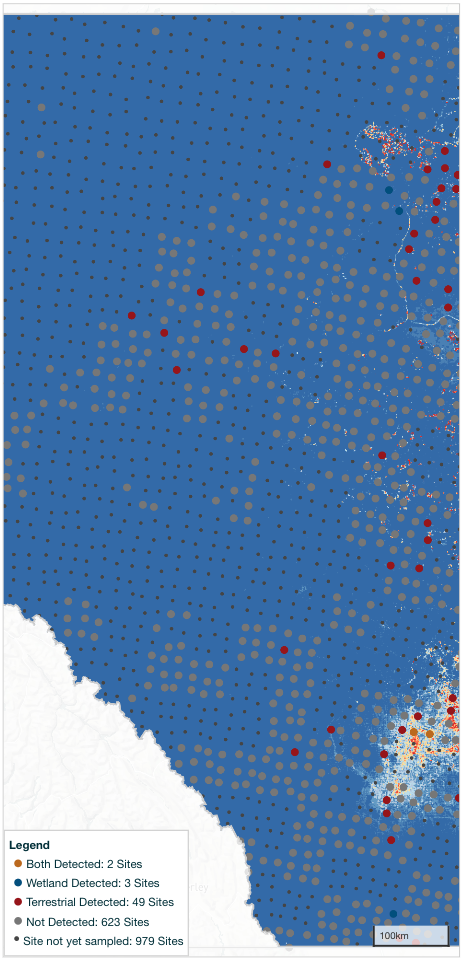

Distribution

- Canadian Toad was detected at 16.1% of 1,648 survey locations.

- Suitable habitat is found throughout the eastern portion of Alberta.

Breeding Habitat

-1.jpg) ABMI

ABMI

Canadian Toad breeds in a wide variety of shallow aquatic habitats in non-forested areas.

(LOW) 0 100 (HIGH)

Seasonality

- Canadian Toads hibernate during the winter, and are only active from May until early September.

- Males begin calling to attract females in May to early July, depending on latitude.

- In Alberta, we detected Canadian Toads vocalizing from mid May to mid July, with a peak calling frequency in early June.

- Canadian Toads started vocalizing later in the spring compared to other calling amphibians.

We present modelling results for the Canadian Toad in the forested and prairie regions. In both areas, Canadian Toad uses a variety of habitat types but abundance is low in sites with human footprint.

- Canadian Toad occurs in all forest types but is most abundant in young black spruce and young pine stands regenerating from natural disturbance. Abundance declines with forest age in all forest types.

- Abundance is also high in wetland habitats including shrubby bog and fen habitats.

- Canadian Toad abundance is low in all human footprint types except urban/industrial and rural industrial types.

- Canadian Toad abundance is low in recently harvested stands, unlike the Boreal Chorus Frog, Western Toad, and Wood Frog.

- Canadian Toad relative abundance is similar at treed and non-treed sites.

- Canadian Toad is more abundant at sites with native soil types, compared to sites with human footprint in the prairie region.

Introduction

- The Western Toad occurs in all natural regions, but is most common in the Boreal Forest Natural Region.

- It breeds in shallow aquatic habitats with sandy substrates, such as the edges of lakes, rivers, and ponds.

- Outside of the breeding season, Western Toad uses a variety of habitats, especially moist conifer and aspen woods and sub-alpine meadows, preferring areas with dense shrub cover.

- During the winter, Western Toad hibernates, usually in small mammal burrows deep enough to avoid freezing and moist enough to prevent desiccation.

Like most amphibians in Alberta, Western Toad has a short, frenzied mating season.

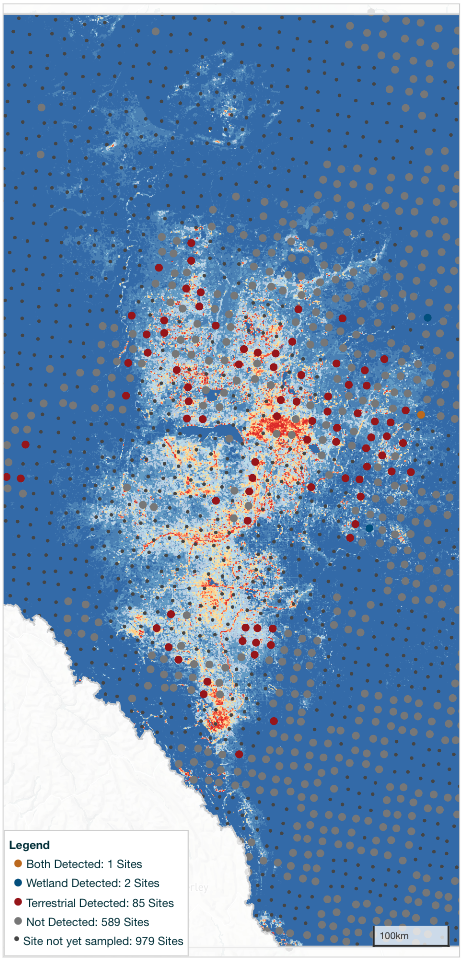

Distribution

- Western Toad was detected at 11.5% of 1,648 survey locations.

- Suitable habitat is found throughout the Foothills and west-central portions of the Boreal Forest natural regions.

Breeding Habitat

Western Toad breeding habitat includes the edges of boreal rivers and ponds.

(LOW) 0 100 (HIGH)

Seasonality

- Western Toads hibernate during the winter, in mammal burrows and other underground cavities.

- They are active from March or April until late September or October, depending on latitude and elevation.

- Males call to attract females during a short period in the early spring.

- In Alberta, we detected Western Toads vocalizing from mid April to mid July, with a peak calling frequency in early June.

We present modelling results for the Western Toad in the forested and prairie regions. In both areas, abundance of Western Toad was generally low in sites with human footprint. Abundance was highest in recently harvested stands in the forested region.

- Western Toad is most abundant in native mid-aged pine and deciduous forests and old black spruce forests; it is moderately abundant in rough and tame pastures.

- Highest abundance was observed in recent harvest areas, which could provide shallow ephemeral ponds that are suitable as breeding sites. However, our models are unable to identify whether breeding is successful in these habitats, or whether they act as population sinks.

- Western Toad is more abundant at treed sites compared to non-treed sites in the prairie region.

- Western Toad is most abundant at sites with rapid drain, thin break, and blow out soil types.

- Abundance is low at all sites with human footprint.

Introduction

- The Wood Frog is relatively common in Alberta and occurs throughout the province, except for the southern portions of the Grassland Natural Region.

- It breeds in shallow, ephemeral wetlands that are free of predators (fish), but may also breed in flooded ditches, road ruts and the shallow bays of lakes.

- When it is not breeding, the Wood Frog is typically found in forest habitats, but also occurs in meadows, pastures and urban areas in close proximity to ponds and wetlands.

- Wood Frogs spend the winter frozen under logs or leaf litter.

Wood Frogs can survive sub-freezing temperatures by increasing the concentration of glucose in their blood.

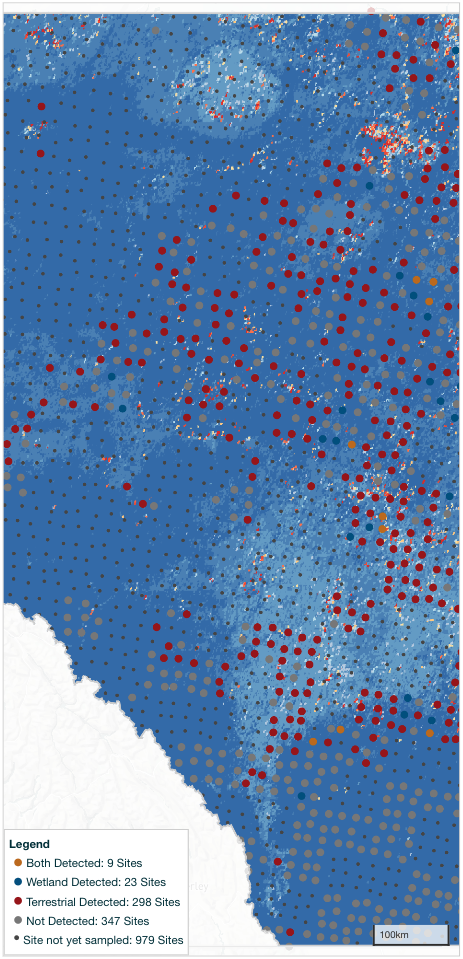

Distribution

- Wood Frog was detected at 41.9% of 1,648 survey locations.

- Suitable habitat is found throughout all natural regions except areas of the Rocky Mountain and Grassland natural regions.

Breeding Habitat

Wood Frog breeds in fish-free shallow wetlands throughout most of the province.

Seasonality

- Wood Frogs hibernate during the winter under leaf litter on the forest floor, and are one of the first frogs to begin calling and breeding in spring, often arriving at breeding sites while there is still some snow on the ground.

- Males call to attract females during a one- or two-week period in April or May, depending on latitude—breeding begins earlier in the south.

- In Alberta, we detected Wood Frogs vocalizing from mid April to late July, with a peak calling frequency in mid May.

We present modelling results for the Wood Frog in the forested and prairie regions. In both areas, Wood Frog abundance is high across vegetation types and human footprint types.

- Wood Frog commonly occurs in all forest types, vegetation types, and human footprint types in the forested region.

- Wood Frog is most abundant in human footprint land cover types including crops, rough pasture, tame pasture, harvest areas, and urban/industrial footprints.

- It is also abundant in native vegetation and wetland (e.g. marsh, shrub, grass) habitats.

- Similar to the Boreal Chorus Frog, the Wood Frog is relatively abundant in young harvest areas. These habitats could have altered landscape properties that allow for shallow ephemeral ponds to form, thus creating attractive breeding sites.

- While the Wood Frog appears to be fairly adaptable to disturbance overall, responding positively to all disturbance types in the forested region, ARU data do not provide information on how successful breeding is at a given site or whether the site is viable in the long term.

- Wood Frog abundance is higher at treed sites compared to non-treed sites in the prairie region.

- The Wood Frog is most abundant in sites with loamy, sandy/loamy, and clay soil types.

- It is also abundant in all human footprint types.

Four amphibian species were rarely detected: Columbia Spotted Frog (Rana luteiventris), Great Plains Toad (Anaxyrus cognatus), Northern Leopard Frog (Lithobates pipiens), and Plains Spadefoot (Spea bombifrons). Not enough data was available to model species–habitat relationships for these species; occurrence information is presented below.

Columbia Spotted Frog

- The Columbia Spotted Frog—listed provincially as Sensitive—is highly aquatic, preferring cool, permanent waterbodies in alpine and subalpine forests; it hibernates underwater during the winter.

- The Columbia Spotted Frog was detected at 2 of 1,648 survey locations, both in the southwestern portion of the province.

Great Plains Toad

- The Great Plains Toad—listed provincially and federally as Special Concern—has three main habitat requirements: shallow, ephemeral wetlands for breeding; upland grassland habitat in close proximity to wetlands for foraging; and loose soil to create burrows for hibernation during the winter months.

- The Great Plains Toad was detected at 4 of 1,648 survey locations, all within the Grassland Natural Region.

Northern Leopard Frog

- The Northern Leopard Frog—listed as Threatened provincially and Special Concern federally—can be found in a range of habitats, from prairies to woodlands, often at large distances from water.

- The Northern Leopard Frog was detected at 1 of 1,648 survey locations, within the Canadian Shield Natural Region.

Plains Spadefoot

- The Plains Spadefoot—provincially listed as May Be At Risk—lives in drier prairie ecosystems with loose, sandy soil, and spends most of its time underground.

- The Plains Spadefoot was detected at 11 of 1,648 survey locations, all within the Grasslands Natural Region.

Detections of the four uncommon amphibians species in Alberta from 2013 to 2021 at ABMI and Bioacoustic Unit locations. Some detection points overlap. Click on the legend to turn occurrence layers on and off.

Acknowledgements

After many years of work, we are pleased to release our amphibian models to the public. We would like to acknowledge all of the ABMI staff that helped improve these models, as well as our expert review panel that donated their valuable time and expertise to improving our models. We are excited for the future of amphibian monitoring here at the ABMI.

Northern Leopard Frog

References and Additional Resources

References

Alford, R.A. and S.J. Richards. 1999. Global amphibian declines: a problem in applied ecology. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 30(1):133-165. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.30.1.133.

Simmons, A.M. and P.M. Narins. 2018. Effects of anthropogenic noise on amphibians and reptiles. In: Slabbekoorn, H., R. Dooling, A. Popper and R. Fay (eds). Effects of anthropogenic noise on animals. Springer Handbook of Auditory Research, vol 66. Springer, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-8574-6_7

Alberta Biodiversity Monitoring Institute. 2019. Terrestrial ABMI autonomous recording unit (ARU) and remote camera trap protocols. Version 2019-12-21. Available at: https://abmi.ca/home/publications/551-600/565

Alberta Biodiversity Monitoring Institute. 2022. Using autonomous recording units to develop species distribution models for vocalizing amphibians in Alberta, Canada. Alberta Biodiversity Monitoring Institute, Alberta, Canada. Available at: https://abbiodiversity.github.io/AmphibianModels/

Additional Resources

Alberta Biodiversity Monitoring Institute. 2022. Using autonomous recording units to develop species distribution models for vocalizing amphibians in Alberta, Canada. Alberta Biodiversity Monitoring Institute, Alberta, Canada. https://abbiodiversity.github.io/AmphibianModels/

Alberta Biodiversity Monitoring Institute. 2021. Biodiversity browser. https://beta.abmi.ca/biobrowser

Canadian Herpetological Society. 2022. Amphibians and reptiles. https://canadianherpetology.ca/species/index.html

Contributors

Brandon Allen, Senior Terrestrial Ecologist, Alberta Biodiversity Monitoring Institute (ABMI)

Brandon joined the ABMI in 2016. He currently leads the development of multiple landscape-scale biodiversity indicators and has become passionate about amphibians.

If you have questions about the ABMI's amphibian monitoring program, please get in touch: brandon.allen@ualberta.ca